You might know the south Indian city of Kochi as a trading port along the Malabar coastline. Or as a starting point for a boat trip into the backwaters, or the heritage sites connected to its colonial past. Only more recent, it has become an important hub for international art lovers. The Kochi-Muziris Biennale is totally worth a visit for art professionals as well as enthusiasts.

Since 2012 Kochi has become an important exhibition space for art practice as well as a platform for cultural and social debate among contemporary artists – mainly from India and its neighbouring countries in South East Asia. The biggest regional art biennale is now located on one of the islands of the city, Kochi Fort. After the postponing and virtual versions of the past two years, everyone seemed eager to visit the Kochi Biennale in 2023.

Though the opening 2023 had to be postponed on short notice, and angered many artists who had already scheduled their visits for mid December, the start into the Kochi-Muziris Biennale curated by Shubigi Rao was not only a feast of contemporary art practices in its diversity regarding forms and content but also mirroring and documenting often struggling members of society, in India and beyond its borders.

Focusing on art in social context, with many addressing issues around farmers protests, women’s rights, LGTBQ+, exhaustion of natural resources, climate change, loss of habitat, megacities, the Kochi Muziris Biennale lives up to its reputation of being the „activist artists platform“ – located in the southern state of Kerala, where the central governments arm of India has been less successful than in other states in managing to muzzle dissident voices, who still dare questioning some of its policies and its at time bruising agenda.

Located on the island Fort Kochi – in its northern part Mattancherry – the old town bursts of spectacular 19th century warehouses, some of which are slowly crumbling, when not used by the Biennale. Many of the two dozen art spaces are conveniently located in walking distance or just a short Riksha ride away.

Just as the visitors, the artists are awed by what the zigzag of lanes, trade and housing structures of a bygone area has to offer. Some of them used its walls as their canvas. Walking around in the area, the art visitor has the opportunity to view contemporary art in a historical „outdoor museum“ on the coast of the Arabian sea, a unique setting at least as attractive as the Venice Biennale, but without the art snobbism and massive tourist crowds. Some artists make the colonial history their subject, others stop the falling structures with their intervention and declare it an act of repairing and thus revitalising of public sites, offering multiple readings .

Mattancherry still functions as a trade storage spot for goods, but was also home to a large jewish colony until the mid of the 20th century. Before Indias independence, around 2’500 jews lived in Fort Kochi. Nowadays, the synagogues and jewish quarters have become tourist attractions. One of the houses of a jewish family was also used as an art space during the biennale. The inside of the house as well as the exhibited photographs documented the life and departure of the last remaining members of a once large jewish community, the Hallegua Family, who had become increasingly isolated, since more jewish citizens had left for Israel over the last decades.

While the dominating exhibition venue Aspinwall has an overwhelming number of works in its large exhibition halls, some of the most exciting artworks can be discovered in the off spaces and galleries, who are part of the biennale but curated by guests or local galleries already present in Kochi. The exhibition „A place at the table“ by curator Tanya Abraham, showcasing local and international female artists with works on power struggles and gender identities is one of the best examples for this.

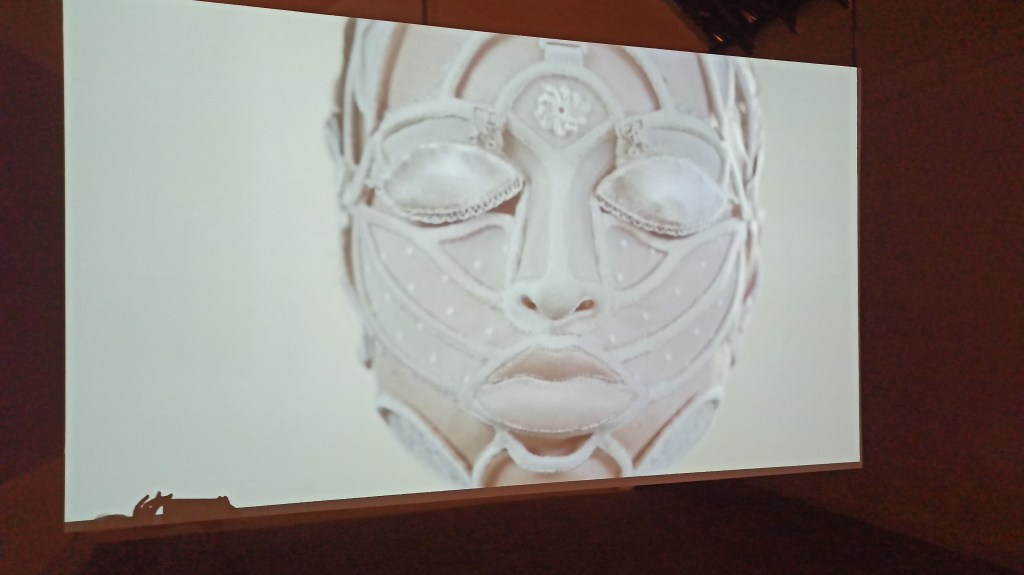

The video „MASK II“ by polish artist Diana Grabowska focuses on a hand slowly undressing a face, covered with parts of erotic lingerie. The slow motion process – somewhat similar to a striptease – glues the spectator to the screen with its striking intimacy, at the same time referring to the veiling of women in patriarchal societies and the „role models“ they have defined for the female gender: you are either a goddess or a prostitute.

The Kochi-Muzirirs Biennale features many local artists from Kerala. One of my favourite works from the main exhibition halls are these two large paintings by Devi Seetharam. A scene from South India, men in conversation in a public space, we only see the lower half of their bodies. Reading the objects in their hands like a tiffin box or an umbrella and the way they wear their white dhoti, we can try to identify their social status and where they are actually standing, in front of a temple or being part of a political rally. Public spaces in India can at specific times of the day occupied by almost all male crowds. Women tied to their duties in the domestic zones, are much less visible in public. Devi Seetharam watches the men, though she deprives them of their full expressions by cutting their upper bodies short. Interesting how the focus of our attention shifts towards a foot held up, or a fold in the tissue from ironing and storing the dhotis. The flower petals on the ground hint to the performance of a Puja – a ritual in Hinduism – nearby.

Another favourite: a video from the Northeast of India – from Nagaland, a remote region bordering Burma, made by Perch, an performance collective based in Chennai. In „U-ra-mi-li“ the artists focused on the collective singing practices in the farming communities during the rice planting season. We watch as the camera follows several groups of men and women as they sing while preparing the soil in the rice terraces and then plant the saplings – a back breaking work. Their songs, rather syllables than words, convert the rhythms of their farming tasks – like shovelling earth or draining water – into hypnotic soundscapes. The entire community is engaged into working in the rice fields, the singing is a community practice passed on orally, reaching back decades. It reminded me of the harvest songs, I had heard a few years earlier during the Hornbill Festival in Nagaland. The video is just one example for the interest by young artists documenting Indian rural customs and traditions in all its diversity.

„Bhumi“ was initiated in Balia, Bangladesh during the lockdown. Local craftspersons worked with artist Kamruzzaman Shadhin to create installations using local materials and agricultural practices. The groups of figures made of sisal depicting scenes from rural life sit on sisal circles hanging from the ceiling. A dramatic lightning puts them on a stage, as the visitor wander among them. Impressive installation and shows the high appreciation of rural handicrafts in South East Asia.

Prasatna Sasu – artist from Santiniketan in West Bengal – created a new body of work „Anatomy of a Vegetable“ as an entire landscape of carefully drafted drawings depicting scenes and practices of rural farm life nearly lost nowadays. Merging scientific drawings with watercolor and acrylic paintings, his eye for details emerges from his own experiences on the farm of his grandparents. He measures the cracks in the dried out earth – result of droughts – as well as documents farming techniques before mechanisation, featuring withered hands of farm workers as tools, thus rolling out a map of the perks and perils of small scale farming in India.